Last week I submited some contribution to an open call launched by LoosenArt who is inviting photographers, video makers and digital visual designers to take part in the collective exhibition “Geographies: an exploration between places, environments and cultures”, an exhibition project that seeks to question and narrate the many forms of contemporary geography: physical and symbolic, human and environmental, local and global.

The aim is to explore borders – geographical, cultural, political, and emotional – and their transformations through the creative gaze of participants.

For this ocasion I dug into my archive and came up with my series “Citiscapes”. Every city has a unique psycho-historical character that reflects its collective memory, culture, and identity. Its architecture, landmarks, streets, and neighborhoods shape its aura and sense of place. A city’s traumas, victories, and transformations are imprinted in its psyche, creating a complex tapestry of emotions and meanings. Understanding the psycho historical character of a city can help us appreciate its nuances, conflicts, and potentials, and foster a deeper connection between its residents and visitors. It also invites us to reflect on the social and environmental factors that shape our urban experience and shape our future cities.

Emotional atmospheres exist constantly and everywhere. Every gathering, even if it is no more than a crowd on the street, is dominated by some sentiment. The emotional atmospheres of a city can be mysterious or specific, incomplete, or complete. They belong to the present and/or the past, and/or the future. They can be fluid or more solid, temporary, or more enduring. Affects can be, and are, attached to things, people, ideas, sensations, relations, activities, ambitions, institutions, and any number of other things, including other affects.

The character of a city is a collection of moments that encompass a range of emotions and events. From the exciting to the heartbreaking, spiritual to adventurous, all these moments come together to form the colorful tapestry of its timeline. Whether its habitants experience happiness or sadness, each piece contributes to the overall mosaic of its psycho-historical map. And while each piece may seem small and insignificant on its own, when seen from a kaleidoscopically perspective, they create a beautiful and unique picture that reflects what it is and the journey it undertakes.

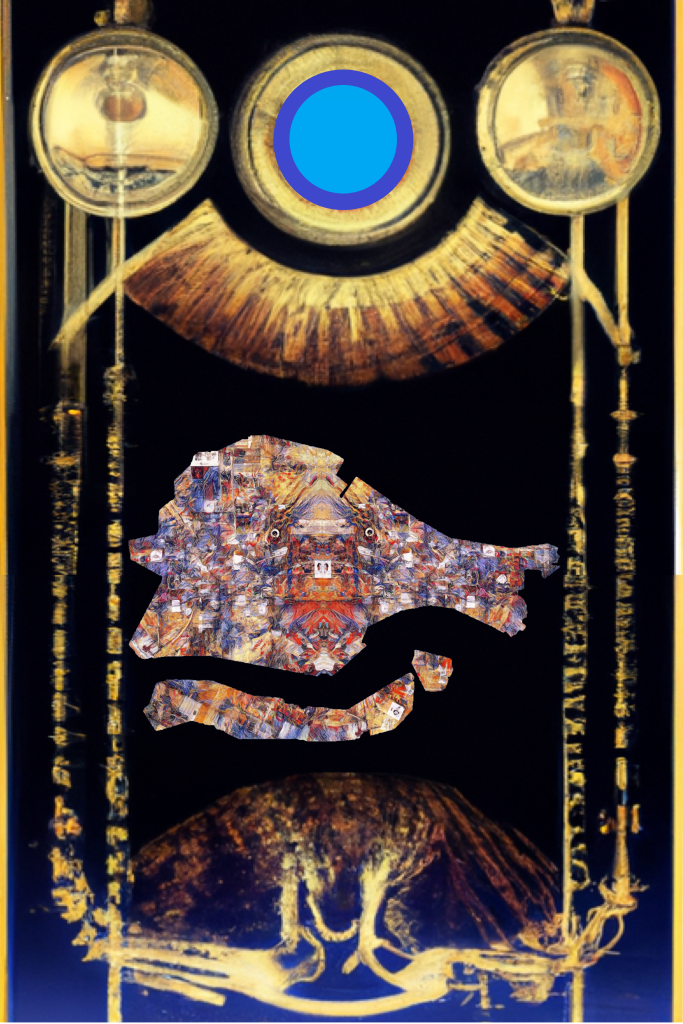

The artwork “Venice: A psycho-historical Map” invites people not to obey existing opinions and common stories about Venice, but to slip away and with confidence listen to their own feelings and play with the city’s atmospheres. The contemporary island of Venice exists in a state of duality, bridging the gap between two pandemics – the Plague and Covid.

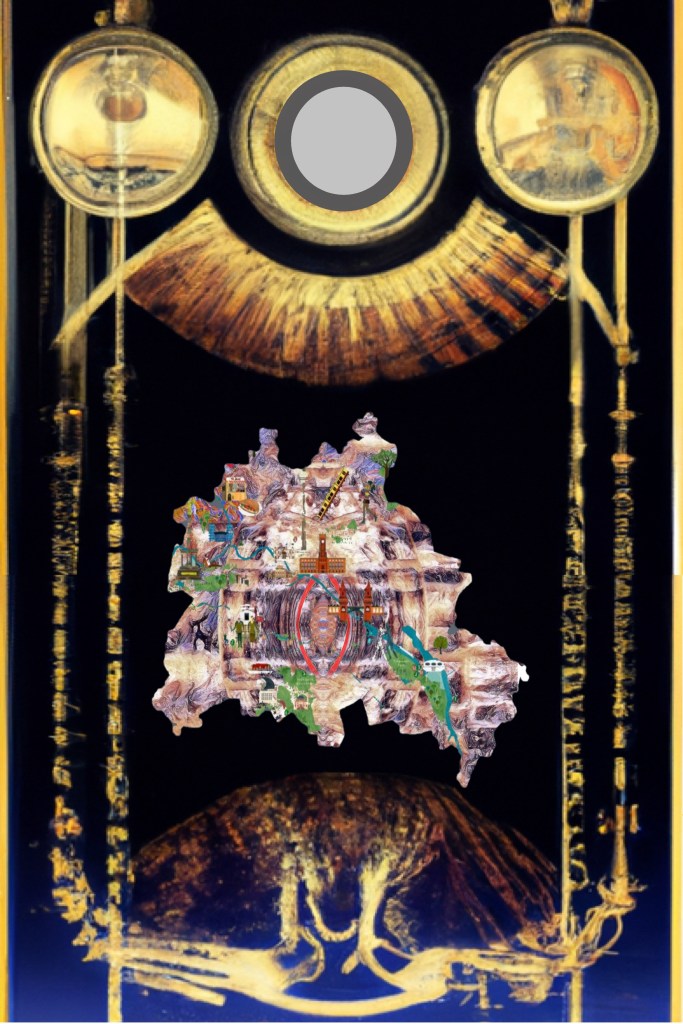

These designs want to break away from a purely geographical representation of a cityscape by introducing the dimension of time into a snapshot.

The concept of these paintings is based upon the premise that cities have psycho-historical contours, with constant streams of movement, fixed points, and fixed angles, which discourage entry or exit from certain zones.

Berlin is damned forever to become, and never to be. From the golden twenties to the anarchic nineties and its status of world capital of hipsterdom at the beginning of the new millennium – the formerly divided city has become the symbol of a new urbanity, blessed with the privilege of never having to be, but forever to become.

Unlike London or Paris, the metropolis on the Spree lacked an organic principle of development. Berlin was nothing more than a colonial city, its sole purpose to conquer the East, its inhabitants a hodgepodge of materialistic individualists. No art or culture with which it might compete with the great cities of the world. Nothing but provincialism and culinary aberrations far and wide. Berlin: “City of preserves, tinned vegetables and all-purpose dipping sauce.”

The history of London, the capital city of England and the United Kingdom, extends over 2000 years. In that time, it became one of the world’s most significant financial and cultural capital cities. It has withstood plague, devastating fire, civil war, aerial bombardment, terrorist attacks, and riots.

A psycho-geography of London derives from the subsequent ‘mapping’ of an unrouted route which, like primitive cartography, reveals not so much randomness and chance as spatial intentionality. It uncovers compulsive currents within the city along with unprescribed boundaries of exclusion and unconstructed gateways of opportunity. The city begins, without fantasy or exaggeration, to take on the characteristics of a map of the mind.

Particularly over the last 150 years, London has been the site of repeated attempts to comprehend the physical, social and economic fabric of city life through exercises in cataloguing and mapping. These mapping exercises render the city legible and articulate its spaces in textual form. Henry Mayhew’s four-volume work London Labor and The London Poor, the first three of which appeared in 1851 and the fourth, ‘Those that will not work’, published in 1862, was the first of the great Victorian investigations of London. Mayhew’s nod to sociological rigor is to offer a taxonomy of London characters, but his methodological emphasis is on personal witnessing through a series of visits to key areas of the city.

London is one of the oldest cities on earth and is shrouded in mystery and legend. Its history is a popular topic for debates and discussions